Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki and Sharon Lechter is arguably the most successful personal finance book ever written, with over 32 million copies sold since publishing in 1997. Just think, that’s roughly 142 books sold every hour for over two decades! For many people, Rich Dad Poor Dad is the first (and sometimes only) finance book they read. Is Rich Dad Poor Dad truly the best finance book ever written? Or is it just that finance book everyone recommends because it’s the only finance book they ever read?

The long and short of it:

In his book, Kiyosaki makes frequent comparisons of his own well educated but financially illiterate father (Poor Dad) with his friend’s business-savvy and stock market-savvy father (Rich Dad).

Poor Dad…

-

- purchased liabilities and thought they were assets (houses and cars)

-

- treated money like a taboo that shouldn’t be discussed

-

- gave up quickly on the things he couldn’t afford

Meanwhile, Rich Dad…

-

- purchased assets (stocks, bonds, rental units) and diminished liabilities

-

- talks about money, surrounds himself with people who know money

-

- always asks how can I afford that?

To be like Rich Dad, Robert Kiyosaki offers a number of principles which he believes everyone should live by. Most of Kiyosaki’s recommendations are widely agreed-upon financial advice:

“Assets put money in your pocket, whether you work or not, and liabilities take money from your pocket”

… And the rich acquired assets where the poor acquired liabilities. All too often, people assume that an asset is anything that is worth money. We procure cars and designer products, thinking these items are assets by virtue of the amount of money we paid for them. Kiyosaki makes it clear that this is a misconception. If your capital doesn’t grow as a direct result of purchasing it, then it’s not an asset, it’s a liability.

Here we must note that something which may be a liability for one person becomes an asset in someone else’s hands. Say for instance that you know nothing about cars and bought a Honda. 8 years later, you sell it second hand at a quarter of its original cost. That’s a liability. However, say you’re a car mechanic who purchased a broken down Ford, fixed it up, gave it a new coat of paint, then sold it for profit. Now that’s an asset.

“I forbid myself from saying, “I can’t afford it.” I have disciplined myself to ask instead, “How can I afford it?”

This is the difference between a scarcity mindset and an abundance mindset. The way we think and feel about things have a big effect on our actions and our general sense of fulfillment. If we presume that something is out of our budget, we will never make an honest effort at gaining the thing we want. Ask yourself this, “why is it that other people can afford things that I can’t?” of course, for some of them it’s inherited wealth or winning a lottery, but for many others it’s because they believed they can improve their lot in life and then made and enacted plans to achieve their goal. This is the essence of the FIRE movement. FIRE chasers believe that anyone with an income is capable of accumulating wealth through wise investing and careful spending.

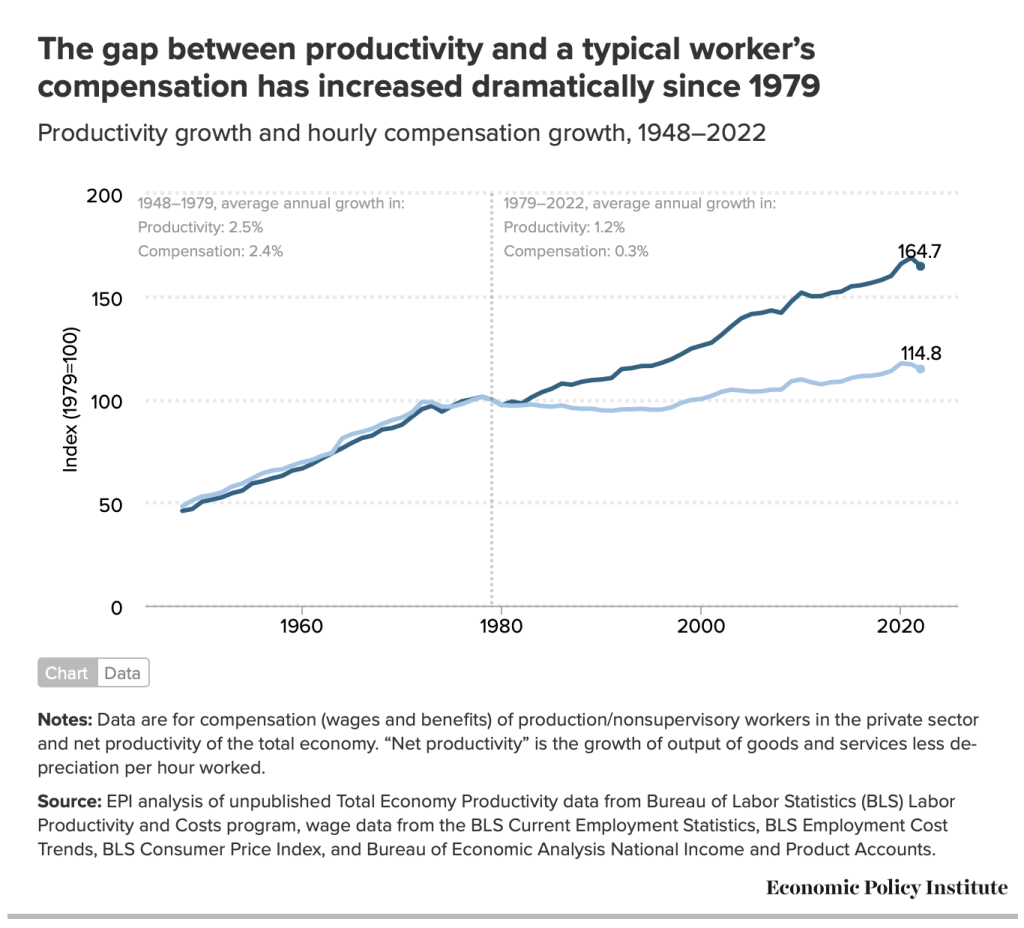

Above is a graph from Economic Policy Institute showing the stark difference between the money you generate for a company and the money you receive in the form of wages. There is more than enough wealth in America to justify every worker getting double their current wage. Abundance is out there, and you’re not about to get it just by working. It’s up to you to open your mind and seize the opportunities.

“The most life destroying word of all is the word tomorrow.”

Thanks to school, most of us think of procrastination as “putting off tasks until just before the deadline,” but what happens if there is no deadline? Procrastination in adulthood looks a little different. While we would never procrastinate on things like paying the bills the like we would our class presentation on The Great Gatsby, we procrastinate on life goals. When we’re given the responsibility to manage our own time, we frequently put off big goals, saying “someday” and “tomorrow,” because as long as we don’t set a tangible deadline, we’ll never be “late” or “overdue.” If we go through life flinching at shadows and backing away from possible failure we will soon find ourselves with no more life to live and little to show for it.

“The single most powerful asset we have is our mind. If we train it well, we can produce enormous wealth”

Before investing in the stock market, we must first invest in ourselves. This advice is very much in line with Warren Buffet’s well-known insistence of staying within one’s circle of competence. By investing in yourself, you expand your circle of competence. There is much to be learned about an industry by working in that industry, much to be gleaned from books for the things you can’t experience for yourself, and much to be said about keeping the company of people smarter than you.

Despite recent advancements in artificial intelligence, the human mind is currently the only intelligence capable of conceiving new and entirely unprecedented ideas. Each and every one of us is capable of enormous creativity and insight. By accepting failure as a necessary part of learning and continuing to hone our mind, we will find that our potential for making money is far greater than conventional wisdom would have us believe.

What makes Rich Dad Poor Dad unique?

Kiyosaki very persuasively and very effectively compares the money habits of his dad, who is poor, and his friend’s dad, who is rich. By putting this comparison at the forefront of his book, he effectively shows the readers what the wrong thing to do is and how to change that into the right thing to do. This way, Kiyosaki establishes something of a roadmap, shining a light on the path to wealth while revealing the potholes that lie along the road.

Aside from the premise, perhaps the most notable idea presented in Rich Dad Poor Dad is Kiyosaki’s second principle: Assets put money in your pocket, whether you work or not, and liabilities take money from your pocket

He specifies that not only should possessions and cars be considered liabilities, a house is a liability as well. “But wait a minute,” I’m sure many people thought as they read Rich Dad Poor Dad, “Don’t houses appreciate in value? Doesn’t that make them an asset, because they eventually put money in your pocket, even if it takes a long time?”

Kiyosaki has this to say: houses are expensive, and today they are more expensive than ever, especially in the cities. Don’t buy a house just because it’s the thing everyone else is doing. Take a good hard look at your own finances and ask if this is something you can actually afford.

Adding on to Kiyosaki’s points, I think we must also keep in mind the numerous dangers of having your money tied up in expensive real estate. For one, houses are very illiquid. Selling and buying houses is such a hassle that most people only do it maybe once in their entire lives. If you need funds for an emergency, it will take months, years even, to make a sale. Another concern is potential depreciation. Just because houses can generally be trusted to appreciate in value due to population growth, it’s not a guarantee. It wouldn’t do to forget the lessons of 2008. And finally, investors need to be aware that even if the house is appreciating, there is an opportunity cost. If you’re going to pour all your savings into an expensive three story for the next 50 years of your life, you had better be darn sure you don’t have a better use for that money in the meantime.

Rich Dad Poor Dad thus asks us to adjust our thinking on assets and liabilities. Although conventional wisdom says houses are assets, this is not always the case. Houses can only put money in your pocket if you sell it for a profit, rent it, or pay off the mortage in timely fashion and live there long enough to save on rent. In any other case, it’s a liability. Making your house into an asset requires taking your income, wealth, and the market cycle into account when you shop for real estate. If you want your house to put money in your pocket, then you need to treat it like an investment, and that means all the research and careful assessment that comes with the territory.

Regarding home ownership, Rich Dad Poor Dad differs dramatically from the majority of finance books. Pretty much every other personal finance book will unequivocally say it’s a good idea to buy a house and own it. For the smart buyer, owning a house means a comfortable and inexpensive place to live after paying off the mortgage and a way to invest your savings so it would appreciate, but for the inattentive buyer, house ownership is a serious liability. As Howard Marks stresses in The Most Important Thing, the safer an investment appears, the more vigilant you need to be for hidden risks. It’s important to know the foundations that lie behind “common sense” practices. If these foundations still hold true for you, then it’s a good idea to buy a home. However, if you have better use for your capital than purchasing an expensive house that you’ll be obligated to pay off over the next several decades, then homeownership might not be for you.

Final thoughts:

It’s probably time I addressed the elephant in the room. Yes, Robert Kiyosaki started several companies, and yes, he did declare bankruptcy for almost all of them. Most of his money today comes from his book sales and for this reason, he is regularly accused of being a fraud who tricked his way into money by selling money advice. I’m of a different mind. I feel that Rich Dad Poor Dad stands very well on its own as a personal finance book. No matter who the advice comes from or what the ulterior motives, if the advice is good, we should take it. Kiyosaki very much takes his own advice. He says “don’t fear failure,” and clearly he is willing to try things that may potentially fail, from starting companies to writing books. Kiyosaki also says “broke is different from poor,” as broke is temporary and poor is eternal. True enough, Kiyosaki’s company went bankrupt, but the man himself never did. He may have been broke, but he was not poor.

So what can we learn from Kiyosaki’s book? Certainly not how to run a business, if the bankruptcies are anything to go by. It’s a credit to Kiyosaki, then, that he never bothered giving business advice in Rich Dad Poor Dad. He instead encourages you to educate yourself, something I am fully onboard with. Rich Dad Poor Dad is most helpful to people at the very beginnings of their personal finance journey, when they’re unsure how to start and need a push to get going. The ideas presented in this book aren’t terribly unique, but the writing is simple and engaging, and the way Kiyosaki presents the well-worn wisdoms of personal finance is relatable and interesting. There is nothing actively wrong with the book, just make sure to keep your wits about you if you decide to read it, and to not take Kiyosaki’s words at face value. You wouldn’t want to go bankrupt after all.

Jenny Xu