While every other investor and fund manager struggled to consistently beat the market (or even reliably turn a profit, as the case may sometimes be), Warren Buffett towers above it all. At the ripe old age of 25, Buffett opened his first, and only, investment partnership, and in the following 13 years (1956-1969), generated a whooping 24.5% annual compounded return where the Dow only produced 7.2% over this same period (source). This impressive track record continues into the present, with Berkshire earning a 19.8% annual compounded return from 1965 (Buffett’s purchase) to 2022 (source). How does Buffett do it? Robert G. Hagstrom, author of The Warren Buffett Way thinks he’s figured it out. Will The Warren Buffett Way teach us how to achieve even a fraction of Buffett’s remarkable return? Or is it trying to sell readers the false hope of replicating Buffett’s unreplicatable success?

The long and short of it:

The refrain of investors who find themselves unable to recreate Warren Buffet’s astonishing success is familiar to us. It must be because he’s an aberration! A genius born at the ideal time with the ideal upbringing who lucked his way into untold fame and riches! Well, Hagstrom replies, there may indeed be luck involved, but it’s no coincidence that Buffett survived six recessions in his investing career (source) and continues to beat the market with a remarkable consistency to this day. Hagstrom maintains that while luck got Buffett started on his path to wealth, it was his skills and adaptability that allowed him to progress as far as he did. In The Warren Buffett Way, Hagstrom lays out the foundations of Buffett’s investment philosophy, his 12 investment tenets, and the psychological pitfalls that prevent the common investors from effectively investing the Warren Buffett way.

Warren Buffett as a synthesis of thinkers

Before getting into the 12 tenets, we must first acknowledge the thinkers that formed the bedrock of Buffett’s investment philosophy.

By this point, I’m sure everyone and their mom knows that Warren Buffett was a keen student of Benjamin Graham. Throughout the years, Buffett has unfailingly paid homage to the man that formed the foundation of his investing philosophy. To this day, Graham’s notion of a margin of safety and the irrational Mr. Market, as expounded in his classic book The Intelligent Investor, remains at the core of Buffett’s methodology.

In contrast to Mr. Graham, most people are far less familiar with the two other central influences on Buffett’s investing philosophy. Charlie Munger, Buffett’s long time business partner and friend, and Phil Fisher, the author of Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and the progenitor of focus investing.

Both Graham and Fisher are big proponents of analyzing stocks as a business, but the two emphasize different aspects of the business. Graham is a veteran of the Great Depression and the trauma of losing almost everything in a devastating market crash has led him to eschew unquantifiable value (quality of managers, reputation of the business, intangible assets, etc) in favor of reliable tangible assets like machinery, securities, and property. Meanwhile, Fisher stresses intangible assets. Beyond conducting thorough research of a company’s finances (present and past annual reports), Fisher also puts great emphasis on personally speaking with the company executives, workers, suppliers, competitors, and clients in a way Graham would assume to be a waste of time. Because such exhaustive research is so time-consuming, Fisher recommends investing in approximately 10 companies, irrespective of industry and diversification. Here too, Fisher and Graham differ in an approach, as Graham recommends investing in 10-30 select companies, each an undisputed industry leader.

Complimenting Graham and Fisher, Munger gave Buffett a perspective of short term volatility as price for long term gain. In the first decade of their friendship, Munger’s investing style leaned towards Phil Fisher where Buffett was a firm Grahamite. It’s largely owed to Munger’s influence that Buffett was able to shift away from his Graham-centric thinking and recognize that there is more to investing than hard numbers and cigar butts.

The 12 tenets and how to apply them

In his many years of following Buffett’s investing, Hastrom was able to compile a set of 12 tenets which encapsulates Buffett’s approach. While Buffett does have a lot of flexibility in his investing and has in his long and illustrious career made a wide variety of investments, all his major purchases bear the hallmarks of these 12 tenets.

Business Tenets

-

- Is the business simple and understandable?

This calls back to Buffett’s infamous circle of competence. The investor must be able to assess the business before they can pass judgment on its performance. A business that you don’t understand and don’t think is simple is not an investment, but a gamble. The idea of thoroughly understanding a business and cultivating a circle of competence has its roots in Fisher’s philosophy.

-

- Does the business have a consistent operating history?

This is the basic requirement of stability, profitability, and a vital part of assessing intrinsic value. Do note though, that this tenet is sometimes negotiable, depending on the circumstance. Buffett invests in people, not entities. What matters more is the quality of the business managers and CEOs, not the corporate entity. If the CEO has a consistent operating history and adheres to the management tenets, then Buffett is occasionally willing to overlook an inconsistent operating history.

-

- Does the business have favorable long-term prospects?

Absolutely non-negotiable. If a business has no prospect for growth, it is not a good investment. Assessing this mostly comes down to understanding the market, the potential for market growth, and the business’ capacity to capitalize on these advantages.

Management Tenets

-

- Is management rational?

Buffett defines rationality as two main imperatives: generating and maintaining profit. To generate profit, CEOs should have a goal of maximizing profit margins, and cutting costs. To maintain profit, CEOs should seek to effectively reinvest their profits by boosting the aspects of their company that are most profitable. When no opportunities for effective reinvestment are present, the rational CEO will buy back outstanding company shares to raise the value of the company’s stock and give excess profit to shareholders as dividend. Many CEOs commit the folly of blowing excess capital on low-return acquisitions and buttressing inefficient avenues of business, squandering wealth and diluting the company’s profit margin.

-

- Is management candid with its shareholders?

Perhaps in part due to his upbringing, Warren Buffett highly values integrity. In a shareholder meeting, the management should be equally as honest when reporting details of their success as their mistakes. This honesty demonstrates an acceptance of responsibility and a commitment to improvement.

-

- Does management resist the institutional imperative?

Buffett believes in the importance of what he calls the inner and outer scoreboard. An inner scoreboard is when you are driven by standards that you have set for yourself, Warren Buffett follows an inner scoreboard and he is not easily persuaded by public opinion and the market pricing of stocks. An outer scoreboard is when you are driven by standards others have set for you and it leads to herd-like behavior where you blindly copy your peers without first thinking through the logic behind their behavior. Frequently, money managers and business executives are guided by an outer scoreboard. They would rather fail conventionally than succeed unconventionally. The CEO of a company must have an inner scoreboard and be prepared to do counterintuitive things to do what’s truly beneficial for the company.

Financial Tenets

-

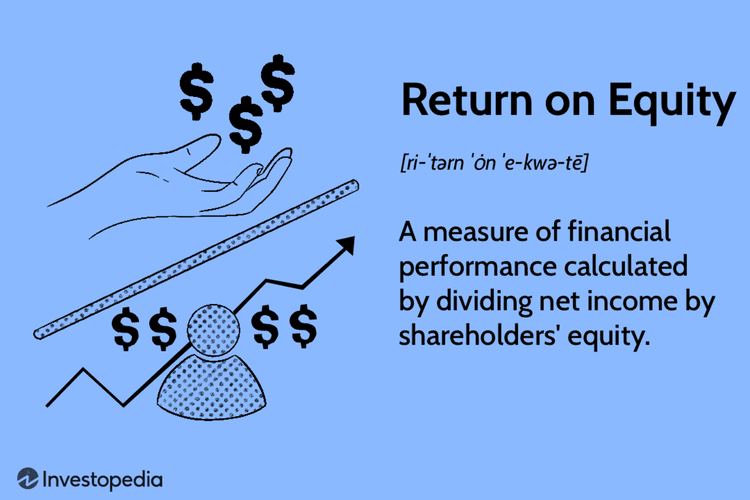

- Focus on return on equity, not earnings per share.

Earnings per share value is an inaccurate metric and should not be used to calculate a company’s intrinsic value. Earnings from previous years are frequently retained which can distort the perceived growth of company profits. Return on equity is a superior metric.

(source)

-

- Calculate “owner earnings.”

Owner earnings is a method of company evaluation devised by Warren Buffett himself. This method was first publicized in Berkshire’s 1986 annual report. The formula for calculating owner earnings is thus:

Owner Earnings =

-

- reported earnings + depreciation (loss of asset value over time, say a rusting oven)

-

- amortization (periodic repayment of a loan over time)

+/- other non-cash charges (reductions of value that doesn’t translate to cash flow, such as depreciation, depletion, and amortization)

– average annual maintenance capex needed (necessary recurring expenses required for a company to maintain operations and sustain growth)

– additional working capital needed (working capital = current assets – current liabilities)

Keep in mind, of course, that the final number this calculation yields is not going to be a precise calculation, especially as average annual maintenance capex, aka capital expenditures, and additional working capital are both estimates pertaining to the future. The owner’s earnings is meant to provide investors with a general idea of value, not a strict number.

-

- Look for companies with high profit margins.

This is a reiteration of the importance Buffett places on rational company managers. Managers with high expenses will always find new ways to add to the overhead while managers with low expenses will always find ways to further reduce cost. This is a matter of temperament and habit. Businesses with a wide moat (a unique competitive edge in the form of intangible assets like brand name, customer loyalty, pricing power, and secret recipes) will also contribute to long term success and high profit margins.

-

- For every dollar retained, make sure the company has created at least one dollar of market value.

A spin-off from the tenet on high profit margins. Companies that have the capacity to reinvest their earnings to boost business (which, in the long-term, translates directly to higher market price for company shares), should do so. This means upgrading their factories, expanding their labor, or clever business acquisitions. If the company is unable to do so, then the profit earned should be passed onto shared holders in the form of dividends or buying back outstanding shares.

Market Tenets

-

- What is the value of the business?

The value of a company should be calculated as one calculates the value of a bond. By treating future dividends and the projected growth as the coupon, the value of the stock can be roughly derived. Additionally, Buffett employs a margin of safety by deducting the long-term US Treasury bond rate from his calculations. Adapting this technique to the current economy, as the return on US Treasury bonds is lower today than in the past, it may be wiser to add an additional 5% to the present bond rate. One can never be too safe.

-

- Can the business be purchased at a significant discount to its value?

With the value of the business thus (conservatively) calculated, we can figure out if the shares are selling at a discount. As always, Buffett says it best, “value investing is buying a dollar for 40 cents.” It’s not always possible to find a good deal in the market, so that’s why continual research is vital for investors. If out of 10 good companies, only one is significantly discounted (with the margin of safety intact!), then only purchase that one company. Be patient, and keep your eyes peeled for better opportunities.

Market psychology – what to weary of

Overconfidence

Everyone, but investors most prominently, tend towards assuming themselves to be above average. Usually this is an innocent mental fallacy. It’s not a serious problem that most interviewed drivers think they’re above-average when, mathematically speaking, some of them have to be average and below-average drivers. For active investors however, success is defined by beating the market, which means an above-average performance. This leads to a serious case of overconfidence, where investors put too much stock in their incomplete research and knowledge.

Overreaction Bias and Loss Aversion

This is similar to a concept we went over in The Psychology of Money by Morgan Housel, the seduction of pessimism, and the importance of mental fortitude discussed in Howard Marks’ The Most Important Thing. Bad news hurts more than good news helps. In fact, in numerical terms, it hurts about twice as much to lose $100 than it does to gain $100. For this risk to feel equal to your loss averse emotions, you’ll have to gain $200 to make up for the odds of losing $100. For this reason, people have trouble following through on doing things the way Warren Buffett does. Intellectually, they know that long term gain is far more important than unrealized loss, but emotionally, they can’t handle performing poorly for 30% of their investment career so they sell their strong long term positions to make short term profit and hold onto bad positions in hopes of a rebound.

The Lemming factor

If CEOs are susceptible to the pressure to copy their competitors, investors definitely are. It boils down to the fear of missing out and preferring to look dumb alongside everyone else, rather than be the lone fool. Just as Howard Marks said in The Most Important Thing, contrarianism is difficult and uncomfortable. But to get above average returns, it’s a necessary evil.

What makes The Warren Buffett Way unique?

Short of Buffett finally writing a book himself, Hagstrom’s The Warren Buffett Way is by far the best cumulative analysis of Buffett’s overall performance in the stock market. Buffett’s letters to shareholders, while veritable goldmines of information in their own right, is not nearly as readable or as succinct as The Warren Buffett Way. Hagstrom has completed for us the difficult task of collecting all the relevant information on Buffett’s most prominent investments over the years, combing through them for common thoroughlines, and presenting the important takeaways alongside practical background information, a series of case studies, and various psychological downfalls investors need to watch out for if they want to produce even a fraction of Buffett’s remarkable returns.

When Buffett says, “What we do is not beyond anyone else’s competence. I feel the same way about managing that I do about investing: it is just not necessary to do extraordinary things to get extraordinary results,” many people write it off as modesty and the case of a smart person underestimating the true difficulty of things they think are easy. Hagstrom has decided instead to take Buffett at his word, which means there must be an underlying system and logic to Buffett’s investment decisions. And so resulted The Warren Buffett Way.

Final thoughts:

The Warren Buffett Way serves as an excellent resource for anyone looking to improve their stock picking abilities but we must also be vigilant of the limitations of imitation. Buffett, being a world famous investor and multibillionaire, is naturally privy to audiences common investors are not. It’s simple enough for Buffett to call up Tim Cook, the CEO of Apple, and personally assess his competency as a business manager and ask him direct questions about how the business is run. The average investor has no such access. No matter how helpful the internet may be, it’s still a long way from getting an in person audience with the likes of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk.

I don’t raise these points to dissuade you from doing as Warren Buffett does, but to point out the ways we must adapt rather than adopt Buffett’s methods. There are some aspects of his investing technique that you will not be able to replicate. Of course, don’t let your lack of access to CEOs of mega corporations and relative anonymity be an excuse to write off the valuable lessons you can learn from Warren Buffett. Buffett was only able to achieve and maintain his legendary reputation through genuine returns, both before becoming famous and after.

So where does this leave us?

Well, The Warren Buffett Way is a good starting point and it’s short enough (234-320 pages, depending on the edition) that it shouldn’t take too long to get through. I most recommend Chapter 3, when Hagstrom gets into Buffett’s 12 tenets and parts of Chapter 4, for case studies, so you can see Buffett actually applying these tenets.

Jenny Xu